Licoricia was a medieval businesswomen, working mother, and leader in her community. Like many Jewish women of her time, she was highly educated. This enabled her to succeed in a man’s world despite prejudice. She made a major forced contribution to the building of Westminster Abbey and financed many other projects. The Jewish community suffered severe religious persecution and the prejudices formed at that time still linger today. The message of “Love they Neighbour as Thyself” at the base of the statue, shared by Jews, Christians and Muslims, is as important to follow now as it was in her time. By the time of her murder, which was never solved, she was probably in very reduced circumstances following the sack of Winchester in the Barons’ War between 1264-7, and continued persecution. Her son Asher was probably forced out of England with the rest of the community in 1290.

It is not known when Licoricia, whose unusual name is associated with the term “sweetmeat”, was born but she first appears in Winchester in 1234 as a young widow, with three sons and a daughter by her first marriage*. By 1234 she had enough money and business acumen to be operating a money lending business in her own right. She is usually referred to as “Licoricia of Winchester” because Winchester was her main place of business. Jewish business women were not unusual and Winchester boasted a number of successful ones at the time. The education of Jewish women was encouraged and Licoricia would have been able to speak several languages (at least norman french, latin, vernacular english and, it is presumed, hebrew) and would have learnt her trade from her family and community. As records show, she was a formidable advocate. She settled in Jewry Street (then the main north-south thoroughfare) in a stone house on a large plot of land of around an acre on the west side of the street (opposite to where the statue will stand).

Many of Licoricia’s clients were landowners and minor gentry. Her first recorded loan was for a sum of £10 – this would be enough to pay for a new, fully fitted ship. Licoricia married David of Oxford, one of England’s richest Jews, in 1242 (please see the fascinating website on Jewish Oxford). Also an explanation of how he divorced Muriel his first wife with royal assistance: withhttps://www.oxfordchabad.org/templates/blog/post_cdo/aid/708481/PostID/38034

Sadly, the marriage only lasted 2 years as David died in 1244, leaving Licoricia with her new son, Asher. As happened when a windfall to the Crown was expected, Licoricia was taken to the Tower of London.

The Jews paid for many major projects throughout England, including Traitors’ Gate and much of the walls of the Tower of London. Please see https://www.hrp.org.uk/tower-of-london/history-and-stories/jewish-medieval-history-at-the-tower-of-london/#gs.mtle2s. “Building the Tower of London”. Please also see the Jewish Square Mile website, which is uncovering the fascinating story of Jews in London, starting with the Medieval Jewish Cemetery beneath the Barbican (www.jewishsquaremile.org).

“From 1189 to 1290, hundreds of Jews continued to be an important part of the Tower’s history and its construction. Much of the outer walls, including the St Thomas Tower with its infamous Traitors’ Gate, was built with Jewish tax money. Taxation of the Jews was frequent, unpredictable, and excessive.

The Tower of London remains significant physical evidence for the history of the medieval English Jewish community”. Please see this fascinating link and the short video below:

Licoricia was remained in the Tower whilst David’s estate was sorted out. In David’s case Licorcia paid the sum of 5,000 marks (£3,500) and Licoricia herself paid a further contribution of over £2,500 in inheritance tax. Most of the money went to pay for the building of Westminster Abbey and its rich shrine to Edward the Confessor.

The shrine to Edward the Confessor in Westminster Abbey (base).

amanderson2, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Rebecca Abrams writes in our book ‘Licoricia of Winchester: Power and Prejudice in Medieval England’ (p.61/2) that the price Licoricia paid for repurchasing her husband David of Oxford’s estate after his death was 5,000 marks (a mark was 2/3 of a pound). ‘Of this, 4,000 marks was earmarked for the building of a chapel at Westminster Abbey to house a lavish shrine to Edward the Confessor (1003-1066), whom Henry III had made his patron saint. Licoricia was also ordered to pay an additional sum of £2,500 as a personal contribution to the new chapel’ [8]. Of this shrine only the base now exists (above). An important shrine like this was a composite structure. ‘First there was the ‘feretory’ itself, a wooden chest covered with gold or silver plates and enriched with jewels and enamels. Ark-like in form, it had a sloping roof and gabled ends like a miniature chapel, and within it reposed the body or relics of the saint. It rested on a base of stone or marble which was pierced with arches or openings into which crippled or diseased pilgrims wee allowed to creep…’[9].

After David’s death Licoricia formed a close working relationship with Henry III and his Queen Eleanor and relatives. She became a leading figure in the community. Her business went well until the advent of the Barons’ Wars which had a severe detrimental effect on the Jewish community. One spring day, early in 1277 she was found murdered in her house in Jewry Street. As Licoricia was such a prominent Jew, her death attracted a lot of attention, the news even spreading to the continent. The motive for her murder is not known.

Less research has been conducted into the life of Licoricia’s son Asher. Asher is named after one of the sons of Joseph. He appears to have acted as Licoricia’s agent on some transactions. The lives of the Jews were increasingly restricted and he had to move from one town to another as Jews were gradually expelled. It seems likely that he was finally forced to leave the country with the rest of the Jewish community in 1290.

There were many reasons why relationships with the Jews deteriorated in the latter half of the 13th century. First of all, they were taxed so heavily that they became less useful and there was mounting competition in money lending from abroad.

Secondly, they were unpopular with the barons and the increasingly meaningful parliament because they gave the King access to his own source of money.

Thirdly, they were accused of coin clipping and this caused a violent pogrom and many deaths. Although there is no evidence to suggest that Jews were engaged in coin clipping any more than their Christian neighbours, and in fact, as money lenders, it was not in their interests to do so, they were ten times more likely to be accused of it. Anthony Julius (Trials of the Diaspora, Oxford University Press, 2010, p116) writes ‘In the period 1278-9, while there were more Christian convicted defendants than Jewish ones (the ratio was about 5:4), ten times the number of Jewish men and women were executed than Christians. Across a longer period, the second half of the thirteenth century, Christian convicted defendants outnumbered Jewish ones by more than two to one, but the execution rate was about three Jews for every Christian. ….It appears that practically all heads of Jewish households were imprisoned for several months in the late 1270s on suspicion of having committed coinage offences. …In summary, during this brief period perhaps as many as half the country’s adult Jewish males were executed…the greatest massacre of Jews in English history.

Finally, they were unpopular with the Church, who made it increasingly difficult for Jews to survive by banning them from lending money at interest or, for example, from buying food from Christians. Tropes such as Jews killing children date from this time and that of Jews and money was amplified. They also increasingly tried to convert them, and make them wear distinctive badges (also required for Moslems). As they could not farm, they risked starvation. In 1290 Parliament promised King Edward an enormous sum of money to get rid of them. He took the money and expelled the Jews. They were not allowed back into this country until the mid-seventeenth century when, inter alia, just as William the Conqueror had done, they were invited back in to increase trade.

Anglo-Jewry wrote poetry, and maintained close links with France, Germany and Spain. The following poem was composed by Meir of Norwich close to when the Jews of England were forced out of the country:

‘The land exhausts us by demanding payments, and the people’s disgust is heard

While we are silent and wait for the light.

You are mighty and full of light. You turn the darkness into light.

They make our yoke heavier, they are finishing us off.

They continually say of us, let us despoil them until the morning light.

You are mighty and full of light. You turn the darkness into light.

When he writes ‘You’ he is referring to G-d.

This was a sad end to the medieval Jewish community and perhaps because of this, its history has been buried for centuries. Small traces however still remain in Jewish tradition, such as the Passover song Ki Lo Na’eh (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G7tAJHt4zbI), first mentioned in the book Etz Chaim by Rabbi Jacob ben Judah of London in 1287, and still sung today.

However, we live in a more open society nowadays and this offers us the opportunity to tell the story of Licoricia as a representative of the community of long ago, and give people a greater understanding of the rich history of the medieval Jewish community, its relationship with Winchester and its royal past and to understand the roots of some of the prejudices against Jews that began in the Medieval era and still exist today. This understanding, we hope, will help to fashion a greater understanding, tolerance and compassion towards the Jewish community and help to reduce all prejudice in our society.

*Asher means ‘happy’ or ‘fortunate’. He is introduced in Genesis 30:13, as a son of Jacob and Leah’s maid Zilpah. On learning of her pregnancy, “Leah declared, “what fortune” meaning “Women will deem me fortunate”. So she named him Asher.” In Genesis 49:20, Jacob prophesies “Asher’s bread shall be rich, and he shall yield to royal dainties”, and in Deuteronomy 33:24 Moses says “Most blessed of sons be Asher; may he be the favourite of his brothers, may he dip his foot in oil”.

Suzanne Bartlet was the first female Leader of Hampshire County Council and wrote the fascinating book ‘Licoricia of Winchester’ (Valentine Mitchell; London, Portland Oregon, 2009). In it she provides a compelling portrait of a lady who was eminent in her time, dealt frequently with Royalty, and whilst being a successful businesswoman in her own right, in her union with David of Oxford married one of the richest men in England. Her husband Leslie collaborated with her in her research and drew her attention to Licoricia. Rebecca Abrams has written an updated book putting Licoricia in context, which is published by the Appeal and available widely.

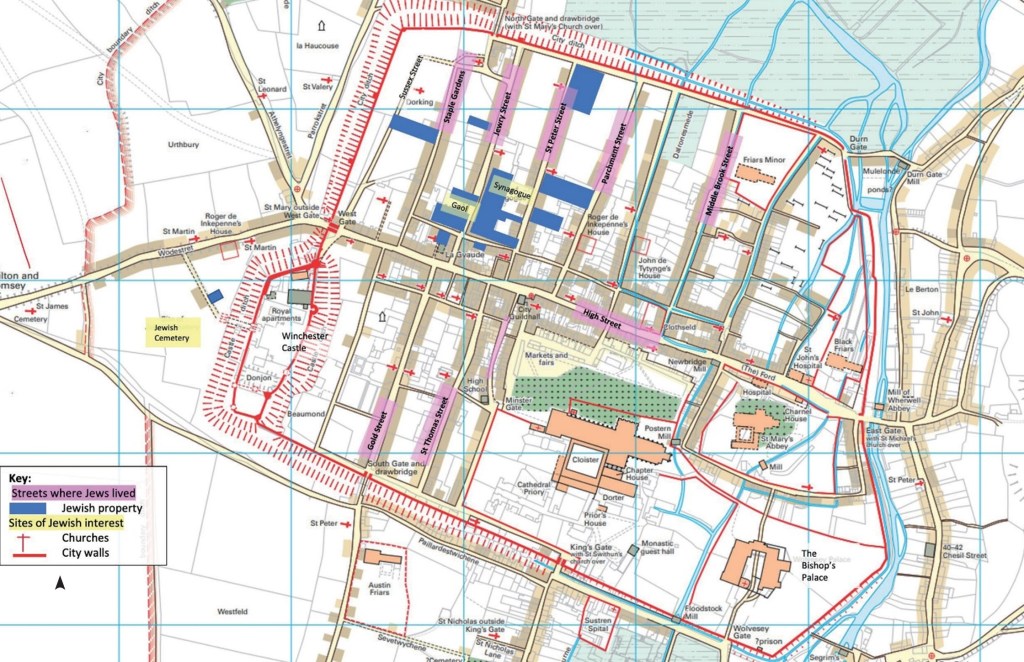

There are many sites of Jewish interest in the City, which is not surprising given the significance and duration of the community in what was then one of the foremost cities in England. These include the Great Hall, where business transactions often took place, the castle, where the Archa containing records of loans was placed, the Cathedral, which contains medieval paintings of Jews, and Jewry Street, where the synagogue was located and Licoricia lived. A Jewish token was found during excavations in Brook Street, Winchester, which is in the care of the Winchester Excavations Committee.

After Map 6, Winchester c. 1300, first published in the British Historic Towns Atlas Volume VI, Winchester © Historic Towns Trust and Winchester Excavations Committee 2017; not to be reproduced without written permission of copyright holders.

A historic map of Winchester is available from the Winchester Excavations Committee.

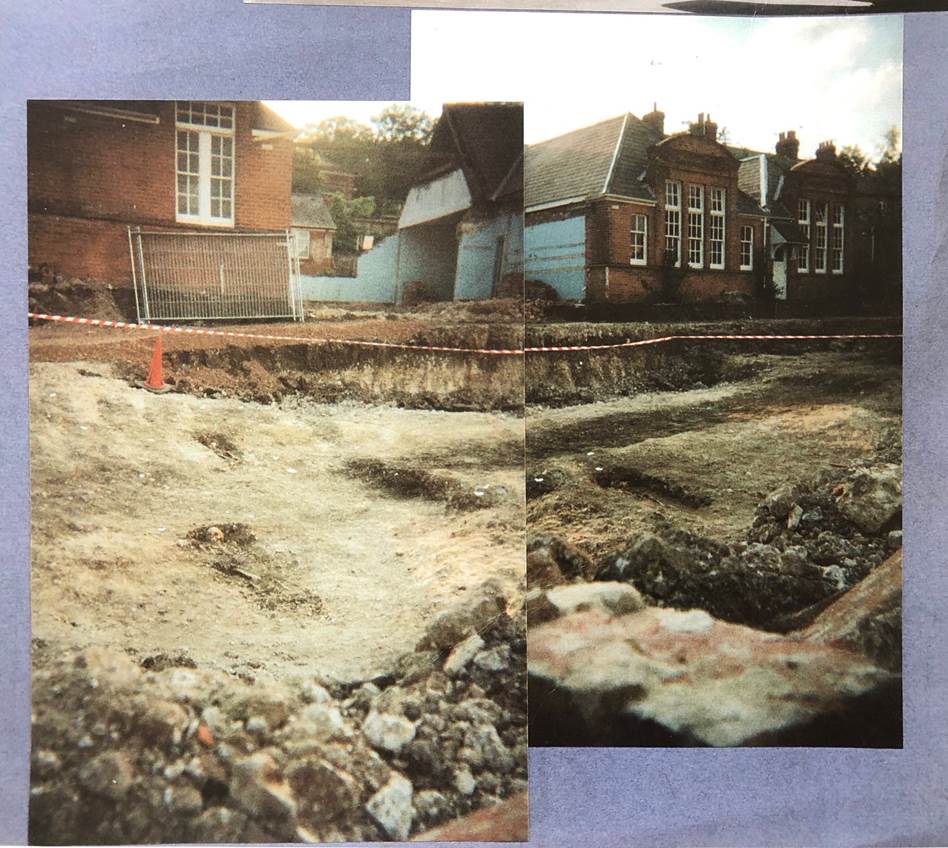

(The image above is of graves in the former medieval Jewish cemetery, taken by Marcus Collins when a building was demolished in Mews Lane in the 2000s).

Background:

The first evidence we have that Jews came over to England in significant number was following the Norman Conquest. They are reputed to have been invited to the country in order to encourage trade. They initially settled in London but by 1159 they had formed nine communities that were self-governing in Jewish matters, one of which was in Winchester. According to Suzanne Bartlet, most historians estimate that the Jewish population peaked at around 5,000 in 1200, compared to a population of around 4-5 million, although some consider this figure to be an underestimate.

The Jews were in a very precarious situation. Jews were to some extent restricted as to the trades they could carry out in this country (they were not allowed to own land for long enough to make it worthwhile for example) but they were in a wide range of trades, such as merchants in wine, wheat and wool; craftsmen in gold, silver and leather; musicians (popular in European Courts – please see https://www.iemj.org/fr/cours-conferences-et-musiques-en-ligne/musiques-juives-medievales.html); much sought after doctors and midwives; scribes and agents; and money lenders. The latter trade came about because certain forms of lending were regarded as a sin by the Church (this developed in the thirteenth century) and Christians were forbidden to engage in them by the Pope. Most credit did not pass through Jewish hands in medieval Europe, however, as the field contained many others including Italians, Christian military orders, Cistercians, and local merchants, moneychangers and bankers. Jews were however able to help provide funds for royalty, and for building castles, cathedrals and abbeys on an unprecedented scale. There were rules governing their lending activities such as a restriction on the amount of interest they could charge and how long they could hold land for once called in for unpaid debt. Jews were required to wear a badge for much of the thirteenth century following the Fourth Lateran Council of the Church of 1215. Europe at the time was part of Christendom in which the Catholic Church had great power and Church and State were not easily distinguished. The Church pressed for action against the Jews in particular because there were few Muslims apart from in Spain and countries like Hungary.

The proportion of the Jewish population engaging in financial dealing is contested, especially given that many were informal or occasional moneylenders, like in the Christian community. Only a few families, probably 1%, were wealthy enough however to be top moneylenders.

The Jewish community provided an important source of private funds for the King and in return were granted his protection in his castles and other sanctuaries when they were threatened. The price for protection was substantial. They were regularly heavily and unpredictably taxed and the King took a proportion of their estate (generally a third but it could be as much as all of it) on death. In this way, they provided a private income for the King and his relatives. Winchester was important in this regard because in early medieval times the Royal mint and treasury was based there. King Henry III was born in Winchester Castle in 1207 and spent much time in the city. Jews providing finance to the king, including Licoricia, would conduct their meetings in Winchester’s Great Hall which still exists today.

For details of the statue and more background please see https://licoricia.org/sculpture/

https://wordpress.com/page/licoricia.org/1375: Licoricia of Winchester